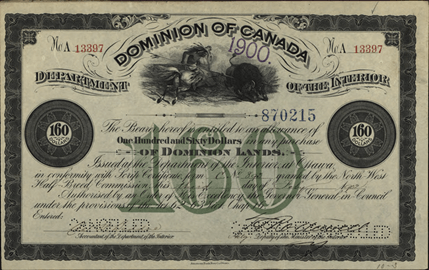

Métis Scrip

What Was Scrip?

The government introduced scrip in the 1870s and 1880s to make land available for European settlers, to avoid creating reserves for the Métis, and to deal with Métis land claims one person at a time instead of as a community. This made it easier for land speculators to buy scrip cheaply and for the government to take over valuable farm land for farming, towns, and the railroad.

Photo Credit: Library and Archives Canada

Métis Land Scrip Document

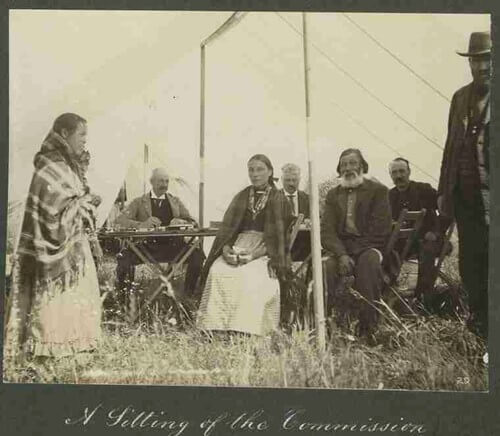

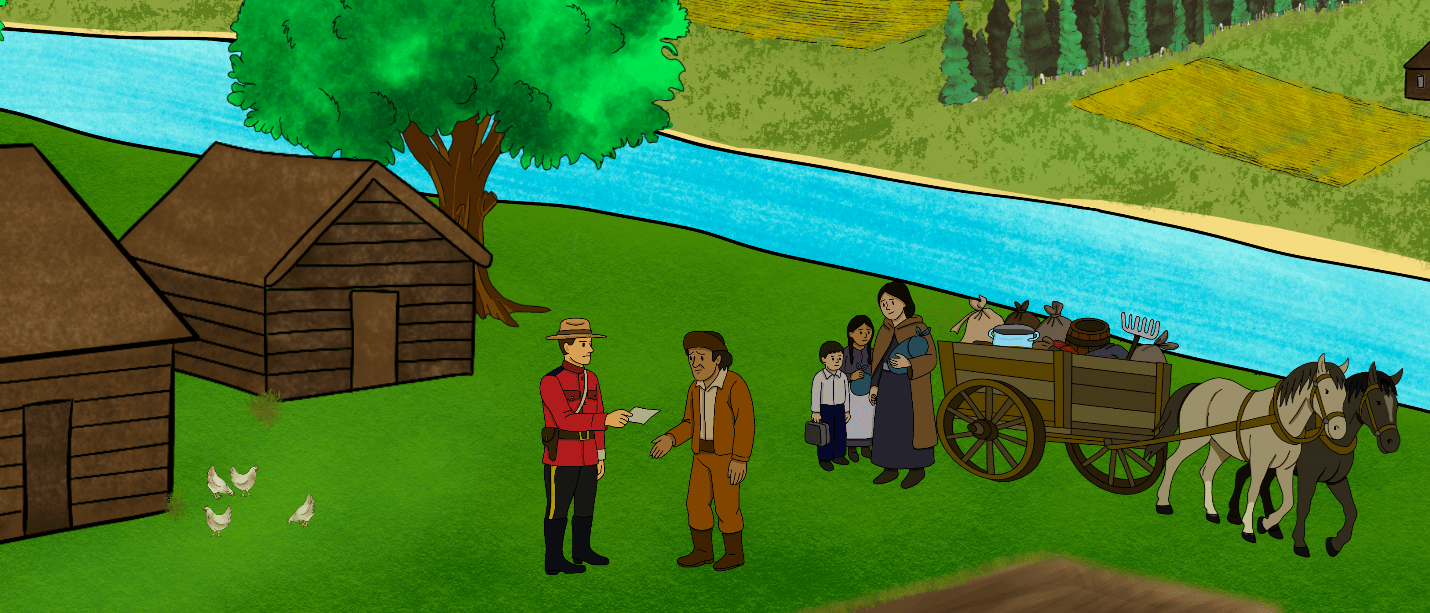

How Scrip Was Given Out

Scrip was handed out in person by government officials called scrip commissioners who travelled to Métis communities. Families had to apply and prove they were entitled to scrip, often by showing baptismal records or letters from church officials. If they were approved, they received either a piece of paper worth land (160 or 240 acres) or money ($160 or $240). To use it, they had to take it to a Dominion Lands Office to claim unclaimed Crown land.

Photo Credit: Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan

Commission members and Métis at Devil Lake, Saskatchewan

Losing the Land

Even though the Métis could use scrip to buy the land they already lived on, this was very hard to do. By the time they received the scrip, much of their land was already claimed for settlers or the railway.

Settlers claimed a lot of valuable farmland land when they moved to Canada

Métis families were forced to leave their existing farms.

Life on the Road Allowances

Some Métis without land moved to road allowances; which were public strips of land set aside for future roads that were 20.12 metres wide. These places had no services, no schools, and people built homes from whatever materials they could find. Life was hard, and they often worked tough jobs for little pay.

Photo Credit: Folklore Magazine, Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society

Road allowance dwelling in west Saskatoon in 1951.